Death of Kapilan Palasanthiran brought change in Toronto's Tamil community

Photo of Kapilan Palasanthiran: Toronto Police Service Website

Kapilan Palasanthiran was a 19-year-old University of Waterloo student when he returned home to Scarborough for his winter break in 1997. The teen went to the Cross Country Donut Shop at 3268 Finch Ave. E. on Dec. 27 and never returned home.

Toronto Police responded to a shooting at the shop at 10:08 p.m. and found Palasanthiran suffering from gunshot wounds inside the shop. Two others were wounded, but the teen died shortly after he was transported to hospital.

The city’s 61st murder of that year remains unsolved.

But his death brought together the growing Tamil community in the Toronto area to deal with the serious problems of youth violence and the pressures of being part of a diaspora fleeing genocide in Sri Lanka and building a new home in a strange land.

Youths at the time, with guidance from the community’s elders, focused their efforts on supporting, driving change and building acceptance through the Canadian Tamil Youth Development Centre (CanTYD).

Abimanyu Singam, a lawyer and one of the founders of CanTYD, described Palasanthiran’s death as a case of mistaken identity.

"He was not a target. It was a mistake in identity, bullets were sprayed on the coffee shop window and the Waterloo student died as a result," he said.

He said the incident was a turning point for the Tamil community, especially Tamil youth.

After the death of Palasanthiran, Singam and a group of his friends along with other Tamil youth from Waterloo University decided to meet and have a conversation about the change needed for the Tamil community.

The youths who met at that time were Renuga Muhuntha, Surendini Pathmanathan, Abarna Puvirajasingam, Luxmy Sanmugasuntharam, Thushyanthy Sabaratnam, Zhivago Marakathalingasivam, Prabaharan Selladurai, Indirakumar (Indy) Pathmanathan, Sivanathan Kathiravelu, Parasuthan Paranirupasingam, Ragulan Thiyagarajah, Saseenthiran Arumugam.

They had the assistance of older community members, Nehru Gunaratnam, Sitha Sittampalam, and Sri Guggan Sri Skanda Rajah who helped them kick-start the formation of the centre, widely known as CanTYD.

It has been 25 years since the group formed CanTYD in 1998, and the non-profit organization is still up and running servicing today's Tamil youth.

Understanding Youth Violence in the Tamil Community

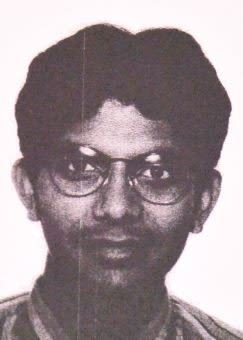

The influx of Tamils in the ‘80s to Canada occurred because of an Anti-Tamil pogrom in Sri Lanka in 1983. The pogrom known as Black July occurred between July 23 and July 30, and about 500,000 Tamils escaped the island seeking refuge in other countries this first mass departure of Tamils resulted in the global Tamil diaspora.

According to PEARL, a non-profit organization which advocates for the human rights of Eelam Tamils, Black July was a vicious genocide promoted by the state.

Explanation of Black July by Pulse.IK

Singam was told by the late Sri Guggan Sri Skanda Rajah, who at the time was on the community advisory council of Toronto Police Services that in the late ‘80s, many Tamil refugees who arrived in Canada were teenagers and young adolescents who were sent to Canada in hopes of a better future and to financially provide for their families in Sri Lanka.

He was told if these young people were lucky, they had extended family or someone from their village who could help them find a job and a place to stay.

"That person would take them give them a meal and the next day they would have to find a job. Wherever they worked they would get the new person a job there," he said.

Singam recalls Sri Skanda Rajah told him in the early years of Tamil immigration there would be a group of 10 to 12 people in one- or two-bedroom apartments where they would sleep on flattened cardboard boxes on the floor.

However, many youths came to Canada alone without any support.

Vathanan Jegatheesan, a community developer said those young men who came without familial support found support in each other to navigate in a new country with new challenges and barriers.

“When these young men came to Canada, they often found themselves having to deal with a lot of racism,” he said. “They were living in marginalized communities, they grouped together in an attempt to look out for one another.”

By the late ‘90s and early 2000s, the Tamil population in the GTA was rapidly growing. According to a York University report by 2001, there were 19,130 Tamils in the Greater Toronto Area.

Gang violence and negative media perception of Tamil youth grew along with the burgeoning Tamil population in the ‘90s. This was when two rival Tamil gangs developed, the AK Kannan and VVT.

The AK Kannan gang was formed in 1992 by Jothiravi Sittampalam. AK stands for the rifle AK-47 while Kannan is a name of a Hindu god and Sittampalam’s nickname. The AK Kannan gang was located in east Scarborough.

Rival gang VVT, which stood for Valvettithurai a town located in the northern part of Sri Lanka. In a 2006 article written by Toronto Star reporter Michelle Shephard, Kaileshan Thanabalasingham was accused of leading the gang which covered the west end of the GTA.

Shephard has written various articles during the ‘90s and early 2000s about the Tamil gang violence in the GTA, documenting criminal activity by the two gangs from the use of weapons, murders, and drug-related crimes.

Criminal activity soared during the decade the two gangs were prominent. They splintered into other smaller but affiliated gangs as AK Kannan and VVT grew.

A 2000 report examining Toronto Tamil youth by CanTYD states by the late ‘90s and early ‘2000s many youths joined the smaller gangs out of loyalty to their friends already in gangs, or because they were assaulted and intimidated by others and sought out the gangs for protection.

Splinter gangs followed the territorial mindset of AK Kannan and VVT, which resulted in the deaths of gang members and innocent individuals.

In a 2001 Toronto Star article by reporters Henry Stancu and Shephard, 23-year-old Sudarsan Velauthapillai who was associated with Silverspring Boys, a gang affiliated with AK Kannan, was shot and killed in VVT territory.

In another article by Shephard, Sandy Ebrahim a 16-year-old was killed because he was standing next to the gang’s intended target. And 18-year-old Sujeevan Sritharan was killed as shooters mistook his identity for a member of GuilderBoys, a gang associated with VVT.

Jegatheesan was a high school student at Albert Campbell Collegiate Institute in Scarborough during the height of gang violence involving the two groups.

He said when A.K. Kannan and VVT members were deported, the gangs collapsed into various smaller gangs, which were the gangs that were around when he was in high school.

"Majority of them were children during the height of gang culture," he said. "They grew up in a world where this was the norm, that being recruited was something they had to do."

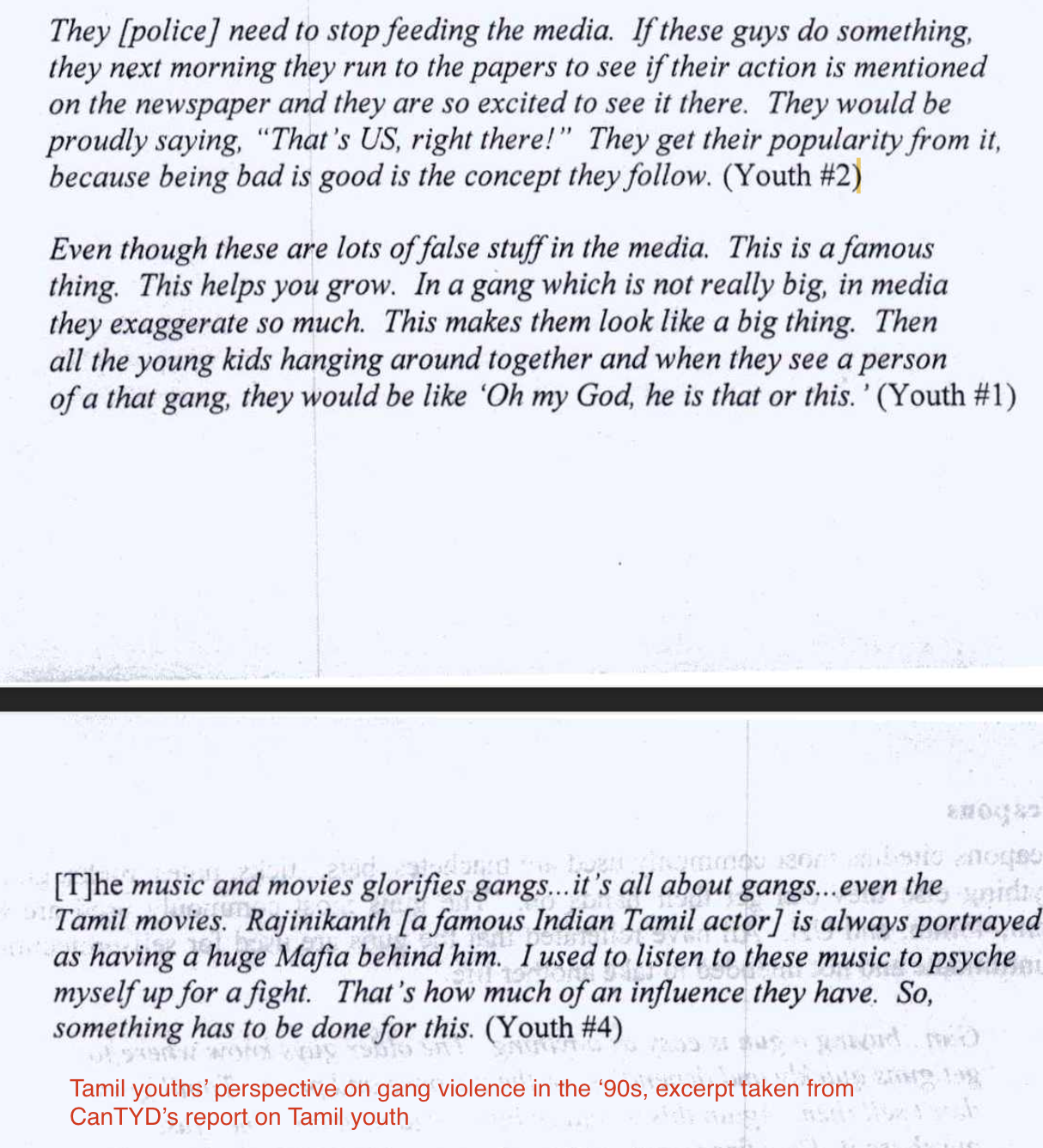

The CanTYD report said many youths in gangs during the late ‘90s and early 2000s were involved with fraud for the thrill and liked the intimidation and fear they created among their community.

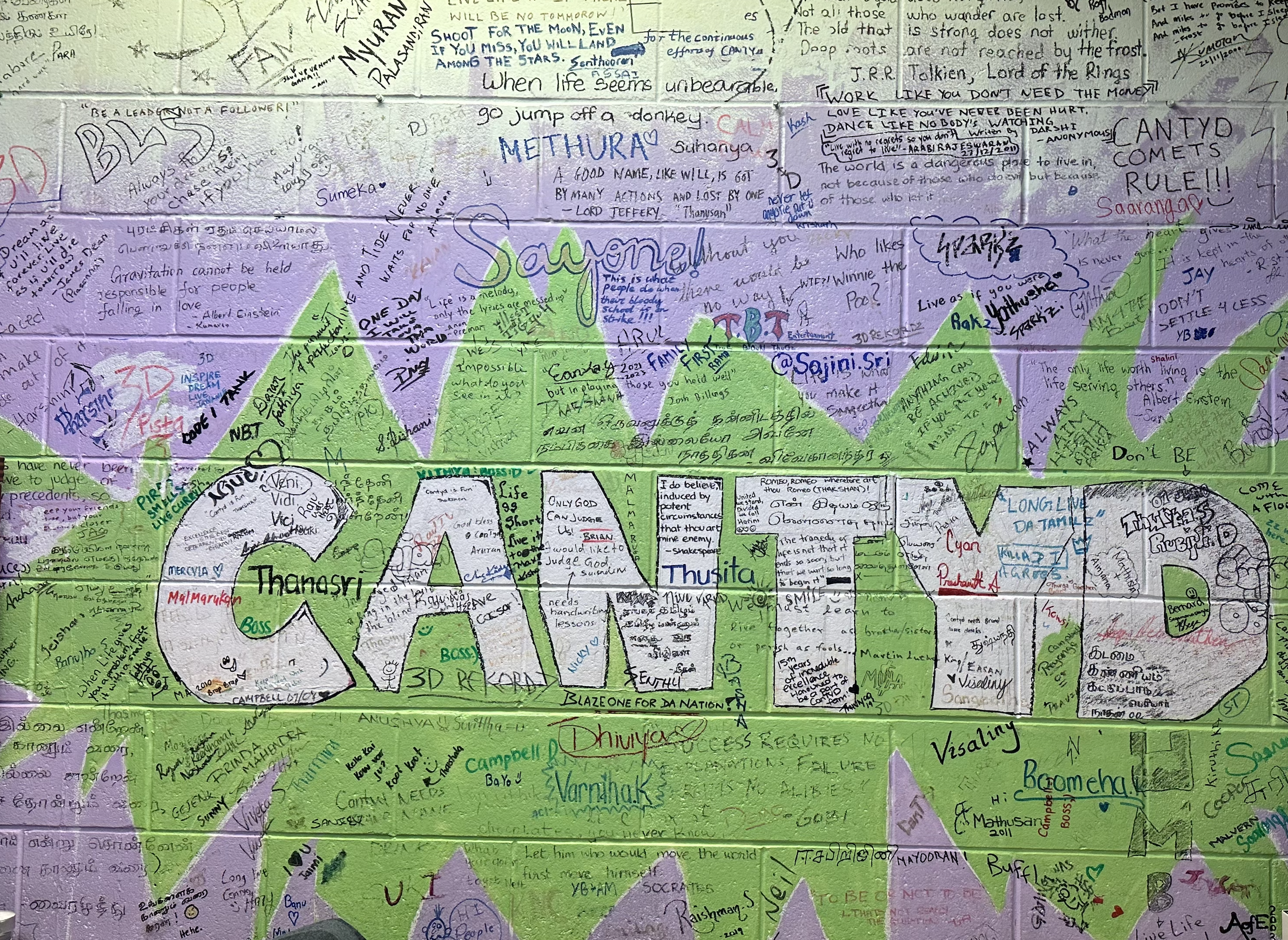

CanTYD has used the same office space for 25 years. This wall has been signed by every youth, volunteer, and staff that was at CanTYD throughout the years.

CanTYD was formed to resolve community issues

Youth violence was no longer gang-centred, the death of Palasanthiran sparked outrage among Tamil youth and highlighted the need for change in the community.

Singam said both the youth and the community recognized something needed change.

“That was a turning point the community and the youth recognized that it was no longer an issue that was limited to the gangs, or the youth that were involved in gang-related activities, it was an issue that was now starting to have ripple effects in the community,” he said.

CanTYD aimed to change the negative perception of the Tamil community in mainstream media.

In a 2001 article by Shephard, police said there were 200,000 Tamils, but less than 100 were involved in criminal activity. But the actions of this small percentage resulted in a negative perception and racism toward the Tamil community as a whole.

Harini Sivalingam, a lawyer and an early volunteer at CanTYD, said she would attend meetings with the media to help them better understand the situations and issues that were occurring in the community.

“ These meetings helped counter the negative perception of Tamil youth being gangsters and terrorists by highlighting the positive achievements of the community,” she said

Sivalingam said a negative narrative portrayed in the media was that Tamil youth violence in Canada was linked to the ongoing war in Sri Lanka.

“The link was that Tamil young people that came from Sri Lanka, are causing a disruption, they’re causing criminal activity here in Canada, and they're using the proceeds to fund the war back home,” she said.

Sivalingam recalls particularly a difficult interaction with the Toronto Sun in the early 2000s.

She said a Sun article that sparked outrage among the community claimed young Tamil women were prostitutes to get money to send back home to fund the war.

“As a young woman, I felt particularly harmed by that media article and the coverage around it,” she said. “CanTYD at that time had a lot of strong young women in leadership roles, and we were outraged by this article that painted us in a negative light and untrue manner.”

She said CanTYD organized a protest in front of the Toronto Sun building to demonstrate that they couldn’t keep publishing untrue stories as it was very harmful to the community.

She said the protest sparked the interest of the Toronto Sun’s editorial board which resulted in CanTYD having a meeting with them. The meeting led to an apology from Toronto Sun and allowed Tamil youth to publish opinion pieces in the paper.

CanTYD then focused on how the Tamil youth, police, and schools were interacting.

Singam said it was to help police and schools understand why Tamil youth were gravitating towards violence.

“We were able to make them understand that this is not anything to do with the civil war and the struggle that was happening in Sri Lanka,” he said. “In a way, it’s a by-product, but it was not necessarily an intended by-product.

“This was an unintended by-product of the immigration that happened,” Singam said.

Suthargini Balasingham an early CanTYD volunteer prepared a report for CanTYD to help police understand the realities of Tamil youth in Toronto. It outlined what frontline workers think are contributing factors to gang violence and compares it to what Tamil youth perceive the factors to be.

The report also listed recommendations for the role schools, parents, media and the police should take to deter individuals from violence and better understand the youth.

Sivalingam also assisted with the report through the writing process and analyzing the data from interviews.

“It intended to demonstrate why Tamil young people joined not necessarily gangs but near-group associations,” she said. Near-group associations are people associated for a limited time with no clear roles, rather than a highly organized group such as a gang.

Sanj Selvarajah, a former CanTYD volunteer, said some Tamil youth mistrusted police due to the circumstances back home with the war, but the police realized partnering with CanTYD would make them more effective.

He said because of the determination of the CanTYD youth at the time, prominent members of the city such as Toronto District School Board (TDSB) superintendent Trevor Ludski, and then Toronto Mayor Barbra Hall, supported their efforts and helped them with outreach to Tamil youth.

Working with the media, police and schools in its early stages allowed CanTYD to become the bridge between the Tamil community and the city. CanTYD created a much-needed conversation in the Tamil community and spearheaded efforts for change.

CanTYD's programs changed the lives of Tamil youth

CanTYD has sparked motivation and ambition in Tamil youth through its programs and events. The main purpose of CanTYD was to provide Tamil youth with the resources they needed, that other community services lacked, and to demonstrate the positive achievements of the Tamil community.

The young individuals who formed CanTYD were university students who were making a name for themselves in the fields of engineering, law, psychology etc.

Gobi Kathirgamanathan a former CanTYD youth and later volunteer said he joined CanTYD as he saw these individuals as role models and people he aspired to be.

“When I joined, it was more leadership, when I saw the people at CanTYD they were in university or finishing university, they were well-spoken and different,” he said.

“That sort of affinity and mentorship that I was looking for that attracted me to CanTYD.”

CanTYD also encouraged youth to try new activities.

Jegatheesan recalls how the centre created a dragon boat race team, an activity many youths did not either think or know about, due to coming from low-income households and being new immigrants.

He said it allowed the youths at the time to forget about the gangs and rivalries and focus on working together to practice for the Dragon Boat race.

“Dragon boat racing wasn’t even something I even conceptualized as an idea,” he said.

“We had to leave Scarborough at 6:30 a.m. and go downtown, and then you get on a boat sometimes with kids you just met and we’re all hustling and working together to practice for the contest, it was definitely a positive experience.”

Kathirgamanathan echoes Jegatheesan’s sentiments he said it was something he’s never done before or even seen Tamil people do, and to him it was inspiring.

“It was inspiring, it was like you don't have to just be studious and you don't have to be a gangster. You could be these other things as a Tamil person,” he said.

Not only did CanTYD focus on exposing Tamil youth to new activities as an organization it pushed for youth to be in leadership roles and build confidence in themselves.

Manjula Selvarajah a journalist and former CanTYD volunteer recalls how CanTYD fueled women's empowerment through leadership roles for women.

She said at that time there were not many Tamil women leaders in Tamil organizations, but CanTYD created space for young Tamil women to take on leadership roles and execute their events and programs.

“There was something about that space,” she said.

“When I walked into this organization, I said I'll help with the Awards of Excellence. They were like run with it, and you get to make the key decisions. It was just like leadership was expected of me.”

Singam said at that time dating was a taboo topic in the Tamil community, and young Tamil men would use forms of intimidation towards Tamil women to date them.

“I have personally witnessed incidents where girls will be walking with their families into events, they will be right beside their parents, and the youth will be catcalling them, they will be touching them, all sorts of things,” he said.

He said for that reason CanTYD focused on creating a safe space for women, by putting women as leaders the organization was able to reflect on the needs of the community from a female perspective and not just a male perspective.

“That was the turning point for our community, leadership cannot only be from one gender it must be a collective,” Singam said. “By providing a space and opportunities for young female leaders we were able to empower not just the community but also females in our community.”

Selvarajah said some of the key programs were run by women which made it difficult for the intimidation of women to take place.

“What would happen is that you might have these kinds of interactions outside when you're on a bus. But when you are in this space, it's tough to be looking at an Akka [older sister in Tamil] and think that you can catcall in a space where an opinionated Akka is sitting across from you, who's pretty much running the show,” she said.

She said CanTYD created women-only discussions as an after-school program, which allowed young Tamil women to express themselves and seek the support they needed.

In addition to exposing youth to new activities and giving them opportunities to be leaders, CanTYD focused on shedding light on the positive achievements of youth through the Awards of Excellence.

The Awards of Excellence is an annual program CanTYD created to acknowledge and celebrate Tamil youth in Grades 9 to 12 for their achievements in academics, community contribution, the arts, athletics, entrepreneurship and most improved.

Not only did CanTYD create a space through the Awards of Excellence for youth to receive recognition for their hard work, but it also allowed them to receive scholarships.

Selvarajah said the first Awards of Excellence took eight to nine months to plan but was a huge success. It was held at Hart House Theatre at the University of Toronto campus with around 400 people in attendance, and then Lt.-Gov. Hilary Weston gave the keynote speech.

Selvarajah said the event was used to push at-risk youth who weren’t in gangs to show them that they can do more and be great.

He said the Awards of Excellence also allowed the Tamil community to be seen in a positive light amid negative media portrayal.

“We wanted to nudge some of these at-risk youth that was in danger of joining the gangs to kind of shift towards more productive and constructive areas,” he said.